Introducing

Science Fiction: A Genealogical Approach

| Science

fiction is a type of formula fiction: |

|

Two enabling

conditions of formula fiction ( e.g. romance, gothic, detective

fiction, science fiction...)

- wide-spread

literacy

- cheap print

formats

|

|

7 traits of

formula fiction:

- The main characters

are parsed into heroes and villains, the good and the

evil.

- Action, incident

and plotting take precedent over ideas or character.

- In formula

fiction the big payoff in reader pleasure comes from the

surprising and wonderful reversal that answers the question

"how will things turn out?"

- Formula fiction

is rife with didactic messages, often enforced by the

plot.

- Formula fiction,

as its name implies, follows pre-established formulas

that require no justification on grounds outside the fiction.

- Formula fiction

accommodates incompleteness, fragmentariness, or last-minute

revision.

- With formula

fiction the basic exchange is entertainment for money.

|

|

Canon Wars:

formula fiction under attack:

- abject status

through comparison with high cutlure

- predictably

mechanistic, trite, and just plain "vulgar:"

Formula fiction

defended:

- high cultural

genres also rely on formulas

- predictability

and repetition are not obstacles to reader pleasure but

its source

- aesthetic

defense: literary writers raid formula fiction for motifs

to incorporate in their "high" art

Q: Questions/

comments? Do you agree with this way of situating science

fiction? Do you see problems with it?

|

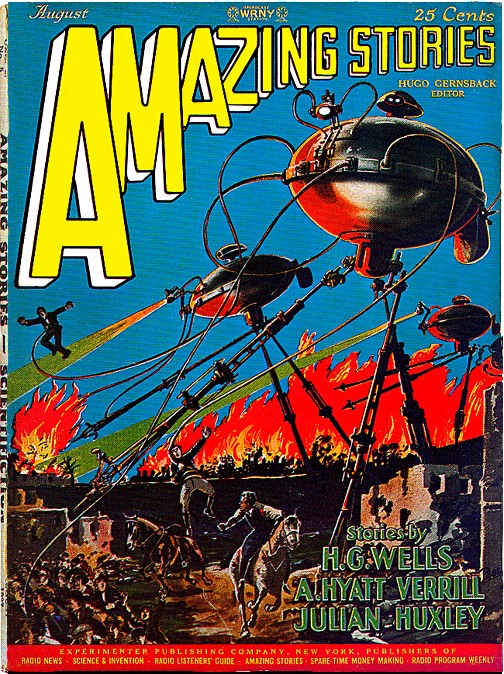

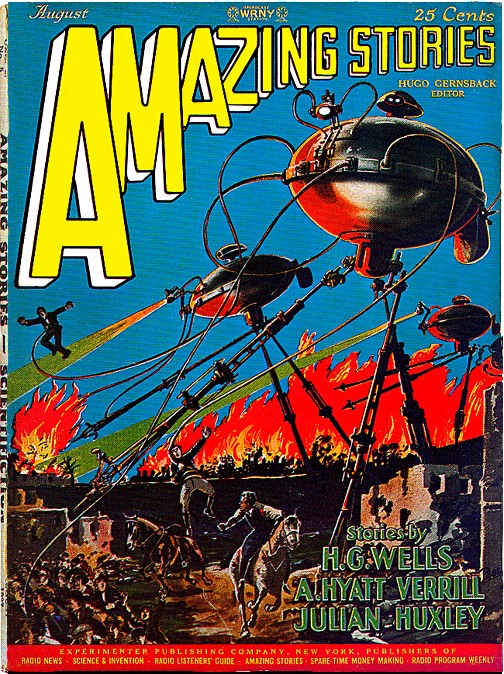

Example: Early

American Science Fiction as Formula Fiction

Hugo Gernsback,

editor of Amazing Stories

- Inventor,

distributor of radio parts, a visionary (one of his stories

predict how radar will work)

- Edits scientific

magazines to educate:

Modern Electronics,

The Electrical Experiementer,

Science and Invention.

Gernsback aims to take his readers beyond stories of fantasy

"to teach the young generation science, radio,

and what was ahead for them."

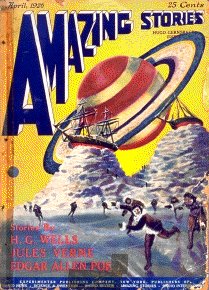

- In response

to reader interest, in 1926, Gernsback gathers "scientifiction"

stories into a new magazine named Amazing Stories.

- The new

format:8X11", cheap paper, gaudy cover art =

100,000 copies sold.

|

|

|

The Cover Art

of Frank R. Paul

How does one

visualize the new worlds of science fiction?

|

| Mary

Shelley, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. (1818) |

|

Myths in the

background

- Prometheus

the fire stealer

- Faust: trading

his soul for knowledge

- willing to

defy conventional limits, and stand utterly alone

- The sublime

landscape of s/f: vast, stark, extreme

|

Frankenstein's scientific question:

"One of the phenomena which had peculiarly attracted my attention

was the structure of the human frame, and, indeed, any animal

enbued with life. Whence, I often asked myself, did the principle

of life proceed? It was a bold question, and one which has

ever been considered as a mystery; yet with how many things

are we upon the brink of becoming acquainted, if cowardice

or carelessness did not restrain our inquiries." (Chapter

4) |

|

After the

success of his experiement, he imagines the gratitude he

will receive:

" No one can conceive the variety of feelings which bore

me onwards, like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of

success. Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which

I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light

into our dark world. A new species would bless me as its

creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would

owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude

of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs."(Chapter

4)

|

|

The Monster

as the prototype of the alien in science fiction

- Technology's

unintended consequences

- Challenges

human primacy and superiority

- Functions

as a mirror

|

|

The monster's

demand of his "Father":

"We may not part until you have promised to comply with

my requisition. I am alone, and miserable; man will not

associate with me; but one as deformed and horrible as myself

would not deny herself to me. My companion must be of the

same species, and have the same defects. This being you

must create." (end of chapter 16)

Frankenstein

destroys the almost completed female "mate" he is making

for the monster:

" I was now about to form another being, of whose dispositions

I was alike ignorant; she might become ten thousand times

more malignant than her mate, and delight, for its own sake,

in murder and wretchedness. He had sworn to quit the neighborhood

of man, and hide himself in deserts; but she had not; …

Even if they were to leave Europe, and inhabit the deserts

of the new world, yet one of the first results of those

sympathies for which the daemon thirsted would be children,

and a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth

who might make the very existence of the species of man

a condition precarious and full of terror. Had I right,

for my own benefit, to inflict this curse upon everlasting

generations?" (Chapter 20)

|

|

The central

moral problem of science fiction

- the attractions

of the powers of scientific knowledge

- unintended

consequences (monsters) & knowledge breeds arrogance

- neglecting

the moral question: is this science and technology

going to promote human good?

|

| Metropolis

(1927): Director, Fritz Lang |

Key features of

the film:

- Biggest budget

film to date

- Science fiction

and the medium of film: a deep affinity

- Dystopia:

Extrapolation from Capitalism as interpreted by Marx

|

Main characters of the film

- John Frederson:

the master of Metropolis

- Freder: his

son

- Maria/ the

robot

- Rotwang: the

"mad" scientist

- Joseph: the

assistant to John Frederson

- Grot: the

foreman

|

|

Scenes important

for the history of science fiction

- Setting: Metropolis

as a the layered city

- The factory

as Moloch

- The metamorphosis

of the robot into a simulation of "Maria"

- Robot/ Maria's

dance (the techno-erotic)

|

|

|