|

English 122: Free Speech, Censorship and Copyright

from the Declaration of Independence to Napster

| Censorship is a Necessay

and Constitutive Part of Culture |

| For most of human history, there has been little

admiration for those who speak freely: propriety and morality

demanded that speakers show respect for one's "betters."

Socrates discovered the danger of teachings that cast

doubt upon authorized religion. Within pre-modern cultures,

censorship of deviant expression seldom needed to be conceptualized

since it was pervasive and implicit. Only with the relatively

recent assertion of a right to free expression, and only

within the public discourse of the modern democracies,

has "censorship" has become a pejorative term--the

C-word. How dare you censor me! This post-Enlightenment

condemnation of censorship usually assumes a conspiracy

against expression directed by a small and secretive group:

like the Star Chamber of the Tudor and Stuart monarchies,

or the Inquisition of the 17th Century Catholic Church.

Yet, the liberal crusade against this restricted

form of censorship does not seem very pertinent to the

more general forms of censorship which appear to

be a pervasive part of culture. Thus, is there any expression

of meaning that does not entail selection and holding

back... and thus a kind of censorship? Is there an occasion

for communication--for example a classroom, a court room,

or a church--that does not presuppose a complex structure

of enabling constraints? Even in our most intimate moment

of expression, when we articulate our desires in dreams

as we sleep, Freud found a struggle between an impulse

to express and a counterveiling need to distort expression

with censorship: "...the phenomena of censorshp and

of dream-distortion correspond down to their smallest

details... " (Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams,

177). Censorship is

also indepensable to good manners: only in moments of

the most extravagant love do intimates imagine they can

say everything to one another. Censorship amplifies

the range of our art by pushing speakers and writers into

that satiric indirection to express that which none are

permitted to say openly. Finally, censorship may be the

handmaden of the erotic. Roland Barthes has suggested

that the eye is drawn to the margin between what is revealed

and concealed, to that artful gap which becomes the site

for the erotic elaboration. Any analysis of censorship

will need to balance ethical complaints against censorship

with an apprehension of the inevitability of censorship

as the ground of any expression. Rather than being antithetical

opposites, censorship and free speech sustain a complex

dialectical relationship: the whole vast realm of the

unsayable carves out a space within which free

speech becomes possible.(Fish) Any astute, and historically

attuned, discussion of policy for new media

like the Web needs to grasp the necessary and inevitable

role for both free speech and censorship. |

| Free

Speech is Our Legally Protected Obsession |

| In the

beginning was speech. The human development of the power

to communicate through speech happened so early in the

evolution of homo sapiens that we know next to

nothing about it.[check] Because the power of speech

is universal across all human cultures, because each

normal human acquires speech so early in life--we call

babies who can't speak, "infants" (from L.

infans, without speech) thus differentiating them from

other humans by what they lack-- speech seems native

to us: hard-wired into our body, our brains, our tongue,

and thus not a system of communication homo sapiens

may have once lived without. The centrality of speech

to humans may explain why speech has become a metonymy

for human expression, as in the phrase, "let me

have a word, please." In the early modern period,

the English political activists Trenchard and Gordan

align speech with the body, property and the self: "...in

those wretched countries where a man cannot call his

tongue his own, he can scarce call any thing else his

own." Cato's Letters (#15, Saturday

February 4, 1720) Within the party politics of the first

half of the 18th Century in England, speech became the

central weapon against tyranny.

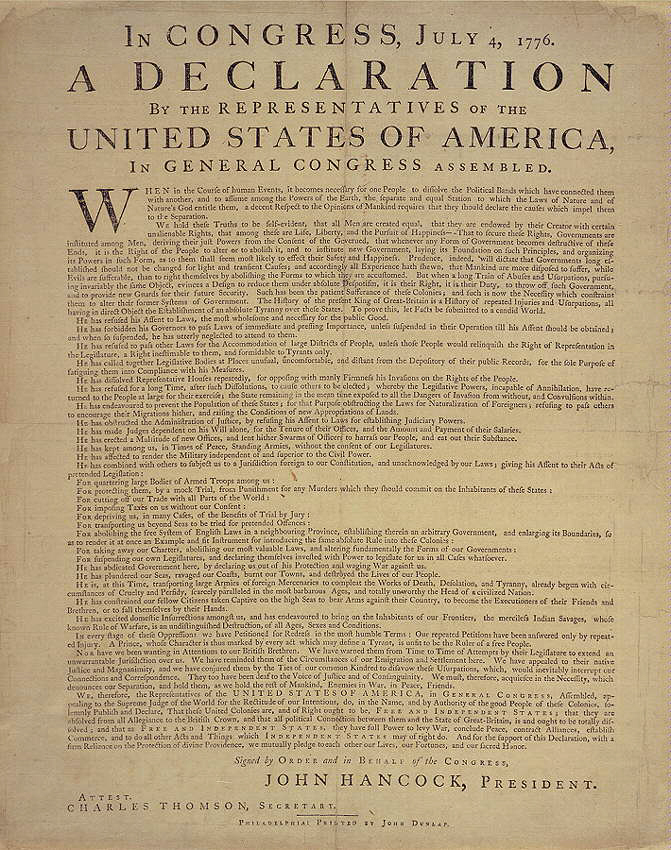

The Declaration of Independence--written

and signed in fair copy, signed, printed, and spread

through the colonies, to be read aloud--began as an

unruly act of speech, and became the origin of the American

nation. It is also an object lesson in the seditious

effect of media. The right to claim freedom of speech

as a natural right acquired legal force through the

Enlightenment revolutions and the Constitutions framed

in their wake. The First Amendment to the US Constitution

has had the practical effect of seeding American political

culture with free speech

incidents: those occasions when those who feel their

freedom of speech has been stifled appeal to the courts

to protect their right to "freedom of speech."

But what is freedom of speech? In the

writings of Milton, Locke and Jefferson, and in the

First Amendment to the US Constitution, this freedom

is often defined in negative terms. For example, the

First Amendment reads "Congress shall make no

law... abridging the freedom of speech or the

press..." One scholar goes so far to claim that

"there is no such thing as free speech."[Stanley

Fish] First Amendment legal scholars avoid the problem

of defining free speech by distinguishing it from speech

that is unprotected by the constitution: sedition,

libel, obscenity, or 'fighting words'; that remainder

of speech "protected" by the First Amendment

is therefore "free." Does freedom of speech

function within our civic discourse as the opaque kernel

of our secular spirituality? as a theater for a heroic

transgression of boundaries in the name of "Truth"?

as the means by which any plain speaker can prove they

are "free?" Is freedom of speech therefore

a romantic illusion? In spite of these skeptical questions,

freedom of speech is the implicit positive term in attacks

upon censorship, and a guiding

ideal for libertarians who dream the future for new

media like the Web. If free

speech has been one of the main ways Americans assured

their participation in public discourse, increasingly

it has also become a way for Americans to claim right

of access to art and entertainment others deem improper

and inappropriate.

|

| Media

is the Matrix for Censorship and Free Speech |

| Between humans and their

meanings are the media of speech, writing, print, photography,

telephony and the broadcast media of radio, television

and the Web. Marshall MacLuhan was one of the first to

note the transformative effect of mutations in media forms:

the modern organization of knowledge depends upon the

printed book and the library; our sense of contemporary

reality is a byproduct of the printed newspaper and television

news; our idea of what it means to be entertained has

been shaped by the cheap paperback book, the phonograph

(from vynl to CD's) and celluloid film. If a mutually

defining relationship between the media of communication

and human culture has been a long standing feature of

human history, one of the cardinal traits of the modern

period has been an accelleration in the rate of the development

and institutionalization of new media. We have been accustomed

to unprecedented change in media. With the invention of

each new medium, the powers at be worry: how will this

challenge our authority? our ability to govern? Is this

new medium a threat to public order and social morality?

At the end of the 20th century, these anxieties have come

to focus upon the Web. At the same time, mutations in

both media forms and the media practices, which are enabled

by new technologies, allow users to expand their role

in the articulation of meaning, knowledge and pleasure.

The struggle between censorship and freedom on the

ground of media appears to be both necessary and interminable.

Rather than consider censorship as an avoidable condition,

or free speech as an absolute right, this web page will

consider several salient episodes in the onging contest

between censorship and

free speech. By considering this struggle across several

different media since the Renaissance, one notes two contradictory

themes: the remarkable persistence of the issues of free

speech and censorship across different media; and, at

the same time, the very different ways media come to be

deployed at different historical moments in different

cultures. This suggests the plasticity of culture and

media, as well as a the value of being inventive and exploratory

in devising new media practices and forms for the Web.

|

| I: A

Global Mutation in Media:the

invention and expansion of print media |

|

- Johann Gutenberg: first bible printed with moveable

metal print 1455

- Luther translates the Vulgate into German (1517--95

theses published)

- Founding of the Papal Index

- Catholic Church demands retraction from Galelio

- Regimes of State Censorship (Francis I of France;

James I of England

- English Civil War de facto lapse of State

censorship

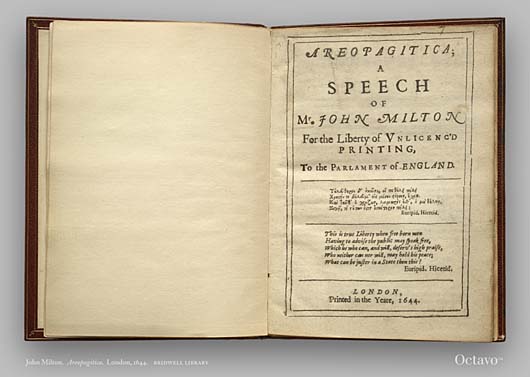

- Milton's Areopagitica: 1644

Many scholars have noted a striking historical analogy:

in 1994, with the arrival of an easy to use graphics

interface for the Internet, the WWW, our culture has

experienced something akin to the movement from manuscripts

to print in the 15th Century. Historians of media differ

on many features of this global mutation in media: on

the character of a culture centered on manuscripts,

on the causal effects of print, on the degree to which

media shapes or is shaped by culture. But there are

three features of this shift that most scholars accept.

Each has important implications for our ongoing institutionalization

of the Web:

- The expansion of the numbers and varieties of

the centers of production: The development and

use of moveable type to print--when coupled with the

whole infra-structure of the print revolution (printers,

booksellers, the postal system, turnpikes, newspapers,

public education, etc.)--greatly expanded the number

of writers and readers and texts. In an analogous

fashion, the Web made it relatively easy to broadcast/publish

from one computer to the millions of linked computers.

- The centrality of the project of transcription:

Print culture does not replace manuscript culture;

instead, the earliest users of print mimiced the genres,

layouts, and letter styles of manuscipts, and transcribed

the content of the manuscript archive into print.

(McLuhan, Eisenstein) Gradually however, the new medium

began to enable media forms and practices entirely

new with print: the printed broadsheet ballad or newspaper,

printed off for an occasion (like a coronation or

a hanging) and circulated to large numbers of readers

within hours of composition; the printing of many

copies of one map so they can be consulted by widely

dispersed users; the compilation of a bibliography

of the ever increasing number of books (Chartier).

- The potential challenge to instituted regimes

of power and knowledge: Try this thought experiment:

Imagine yourself as the ruler of a small kingdom before

the existence of any electronic media technology or

any printing technology. In order to rule your kingdom,

you rely only upon manuscipt writing (of religion,

law, science) and speech (in council, on ceremonial

occasions, and through proclamations). Manuscripts

are rare, expensive, and reserved for important matters;

literacy belongs to a privileged few who can read

and write. Now imagine the arrival of printing and

the opening of writing and reading and the act of

publication to the multitudes. What would be your

media policy?What steps would you take to control

the use of printing?

This thought experiement helps explain the censorship

projects, conceived by the Catholic church and monarchs

like Francis I of France and James I of England, to

contain the menace of print. We late moderns are so

used to a promiscuous glut of print media that it is

difficult for us to understand why so many early moderns

experienced a unsupervised printing as a serious threat

to civilized life. Throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries,

those who framed media policy worried that the spread

of print would expand religious heresy and political

sedition. They were right to worry. The subversive power

of printing is illustrated by Martin Luther's translation

of the Latin vulgate (15??) into German: by delivering

the scriptures into the hands of every believer who

could read in their native tongue, authority over the

meaning of Holy Scripture is dispersed. Little wonder

that the Pope convenes the Council of Trent to combat

this democratization of religion with new systems of

control. Most early modern systems of censorship required

that anyone seeking to print a book--whether the author,

bookseller or printer--receive a license from an officially

authorized granter of licenses. This became the accepted

norm throughout Europe in the early centuries of print.

An Unlicensed Press: History ran an early experiment

in unlicensed printing: during the English Civil War

(1641-1649), when Parliament had won effective control

of London and the Stuart monarchy raised its standard

at Oxford, England experienced a suspension of the informal

system of censorship developed by the Crown and the

Stationery's Company in the first century of printing

in London (Feather). Civil War brought an unregulated

explosion of print--much of it propaganda designed to

advance one side or other in the war. Citizens began

to experience, and perhaps enjoy, unfiltered access

to a wide variety of writing. When the Parliament passed

a new licensing act in 1644, which was modelled upon

that of the monarchy it abhorred, John Milton published

Areopagitica: an Address to Parliament for the Liberty

of Unlicensed Printing. Milton's text outlines

the argument for the system that exists in most of the

liberal democratic states of our own day: a press that

is "free" because there is no "prior

restraint" of the press. In Milton's world of readers,

the critical function of censorship--deciding what is

true and false, good or evil--passes to the individual

reader. In effect, each reader becomes his or her own

censor.

Printing helped to make writing an ambient part of

culture; print became a medium almost as pervasive as

speech. Many in the early modern period still believed

that censorship was possible. But, in fact, if one studies

projects of censorship (from the 17th C. England and

the Old regime in France to modern Russia, China, and

Iran), one finds that censorship almost always fails.

Rather than winning full control of what is written,

published and read (as some may have dreamed of doing),

official censorship becomes an unintended collaborator

of writers. It inflects the character of texts written

in the wake of censorship. See below, movie production

code. |

| Print

on the Market and the Ideal of Public Culture |

|

The Dunlap broadside: print version of the Declaration

of Independence

Holmes: "But when men have

realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they

may come to believe ...that the best test of truth is

the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the

competition of the market..."(Abrams v. United

States, 1919)

Brandeis: "Those who won

our independence by revolution were not cowards. They

did not fear political change. They did not exalt order

at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant

men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless

reasoning applied through the process of popular government,

no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and

present, unless the incidence of evil apprehended is

so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity

for full discussion. ...Only an emergency can justify

repression. Such, in my opinion, is the command of the

Constitution. It is therefore always open to Americans

to challenge a law abridging free speech and assemblly

by showing that there is no emergency justifying it."

(Whitney v. California, 1927) |

- The "Glorious" Revolution, 1688

- Lapse of the Licensing Act, 1695

- First Copyright: Law of Queen Anne, 1709

- Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees, 1704,

1714

- Addison and Steele, Spectator, 1711-1713

- Trenchard and Gordon: Cato's Letters 1722

- Declaration of Independence 1776

- First Amendment to the US Constitution &

Sedition Act 1789-91

How did free speech become a sacred cow and censorship

the "C-word"? In the century after 1688, there

emerged in England and America a liberal democratic

paradigm for conceptualizing the relationship between

censorship, free speech and media. Although this paradigm

has been subjected to probing critique (Gaines),

it continues to provide the terms for many of our contemporary

debates upon the proper uses and abuses of new media.

There are three cardinal elements to this liberal democratic

paradigm: the centrality of a market supposed to be

free; the democratic concept of power as an empty place;

and the radical claim to freedom of speech.

The centrality of a market supposed to be free.

By granting state sanctioned monopolies to guilds

and companies, Renaissance monarchs were able to profit

from those enriched by a monopoly, and sustain a measure

of control over the activities of production. Thus,

for example, the Stationer's Company was given monopoly

control to regulate the patent and copyright of individual

booksellers and printers; in exchange the Company limited

production to a limited number of London booksellers

and exercised licensing powers on behalf of the state.

Here, the regulation of trade and the censorship of

writing go hand in hand. With the lapse of the Licensing

Act in 1695, this formal legal arrangement broke down.

Now protection for those who owned property in manuscripts

was achieved through the first modern copyright law,

the Law of Queen Anne (1709). During this period cultural

observers began to conceptualize the remarkable powers

of an unregulated market. Addison celebrated the ability

of markets to draw every luxury in the world to the

Royal Exchange where common interest would reconciles

the differences of Arab, Jew and Gentile.(1711) Bernard

Manderville isolated the paradoxical moral economy of

markets: private vices (like greed and vanity) fueled

the purchase of goods that produced public benefits,

like unprecedented national wealth experienced by England.

(1704) Over the course of the century, cultural critics

worried that markets in print, through the cumulative

effect of many isolated decisions to buy or not to buy,

effectively circumvented earlier forms of cultural authority

and performed designations of value beyond the reach

of any guiding moral or aesthetic judgment. In the wake

of the new ascendency of the market, the modern struggle

between an improving higher culture and the more popular

insistence upon being entertained,

had been joined.

The democratic concept of power as an empty place.

With the accession of William and Mary in 1688, decisive

power shifted from the individual monarch to an elected

body, the Parliament. John Locke is usually credited

with conceptualizing a newly limited concept of government,

one stated in the 2nd paragraph of the Declaration of

Independence: that government draws its legitimacy from

the people; government only exists to protect the prior

rights of the individual (rights to life, liberty and

property); when a government becomes destructive of

these ends the people have the right to cast aside this

government. There is another way to conceptualize limited

government: instead of the power of the state being

vested literally and symbolicly in the monarch's body,

power was now located in an empty place--the persons

and parties (Tory and Whig) of Parliement.(Lafort) This

deplacement of the monarch's body puts a new importance

upon the public exchange of discourse, whether in the

form of speech, writing, or print. The flourishing of

political journalism--both that sponsored by the parties

in power, and that launched by opposition--becomes the

discursive matrix for this interminable political negotation.

Habermas has described this new political arrangement

as depending upon rational debate in the public sphere--a

medial zone between the State and the intimate sphere

of family and work--where private citizens can confront

the State and freely exchange opinions upon matters

of importance to all. Limited government, the priority

of individual rights, the free exchange of opinions,

broad education of the citizenry, these are the basic

components of the liberal ideal of public culture. This

liberal ideological synthesis relies upon an analogy

between economic and political circulation: the emergence

of a public culture valuing the "free exchange

of ideas" is coextensive with the emergence of

modern unregulated markets for the "free exchange

of goods." (See Holmes.)

In a distinctly British and American ideal of the way

the markets in goods and ideas should work, value (that

is, "wealth" or "truth") appears

to increase through the operation of a market system

that is spontaneous, unsupervised, free and thus "natural."

The radical claim to freedom of speech The expansion

of a public culture depends upon public-ation

in print; but it leads to a claim to the primacy of

the right to speech. Cato's Letters, the influential

political journal of the 1720s written by Trenchard

and Gordon, turns the freedom to speak into a radical

test of a person's liberty and property in himself,

and an indicator of the tyranny of others: "...in

those wretched countries where a man cannot call his

tongue his own, he can scarce call any thing else his

own." The American nation is founded in a spectacularly

successful enactment of free speech: a declaration of

independence from England. By writing, signing, printing

and distributing the Declaration of Independence,

and by successfully countersigning that printed speech

with blood, the "united states of america"

started on its way to become the U.S.A. When the colonies

forged a Constitution to formalize their union, worries

about the abuse of power by this new central government

led to the passing of the 1st Amendment to the Constitution.

There, between the right to practice religion, and the

rights peaceably to assemble and to petition for redress

of grievances, freedom of speech is given protection.

But this "right" is not won through the laws

of the Legislature, but through a law against laws:

"Congress shall pass no law...abridging the freedom

of speech or the press,..." The abstract character

and absolute value given freedom

of speech by the 1st Amendment results in part from

the double negative which protects it from definition

and limitation by the state: Congress shall pass no

law ...abridging it. In practice state courts

and the Supreme Court have been called upon to define

what is protected by this amendment and what is not.

But the process of legal review during the two centuries

since the ratification of the 1st Amendment has not

narrowed what freedom of speech means; instead, judicial

review has led to a dynamic expansion of the concept

of free speech: first, in Madison's and Jefferson's

battle against the Federalist's Sedition Act

of 1798; much later, in a series of cases surrounding

the Espionage Act of 1917 passed to limit protests

against American participation in WWI, Justices Holmes

and Brandeis developed the rationale

for protecting the citizen's right to criticize their

government, even in times of war; finally in 1933, Ulysses

was cleared of the charge of obscenity because of its

"redeeming aesthetic value;" even the right

to take off one's clothes before an audience has been

granted protection under the 1st Amendment.( ) These

legal protections of speech helps explain why our newspapers

daily report what I call "free

speech incidents." These have three component elements:

1: the initial "speech" (the legal term for

any act of expression) of a citizen; 2: some sort of

action taken to punish speech and/or close down the

space for further speech; 3: an appeal to a higher authority,

usually a court, to recognize this punished speech as

protected by the 1st Amendment of the US Constitution.

|

| III: Photography

and the Shock of the Actual: the

Case of Robert Mapplethorpe |

- 19th Century photography--for porn, for portraiture,

for identification of criminals

- The "brownie" and catching Kodak moments

- Robert Mapplethorpe's "X Portfolio" and

the NEA: a case study in the shock of the actual

- the digital mutation: the image no longer indexes

an antecedent object or a moment

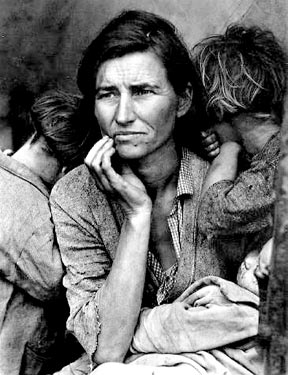

Narrative: Photo-graph is Greek for "light

writing." In the early days of photography many

argued that copyright over a photograph was impossible

because the image was "drawn" by "nature."

To this day the power of the photograph consists to

its evidentiary power--upon the notion that upon the

photograph there is a trace of the actual object and

a moment of inscription deposited upon the negative

and rendered visible on the positive copy of that negative.

That is why photographs can be entered into court as

evidence of a crime: it produces produce proof of some

thing "there" at the time and place of the

inscription of the image. This famous photograph of a migrant mother during the

dustbowl migrations of the 1930s is an outstanding example

of this sort of photograph. Many of the earliest uses

of photography suggest the power of this inscription

of the actual upon film: pornography etches the nakedness

of an actual model into an image, the portrait captures

a unique individual, and a compiled inventory of mug

shots can aid in the identification of criminals.(T.

Gunning) New technologies extended the reach of the

photograph: the cheap Kodak camera enabled millions

of amateurs to become photographers of the intimate

family life; the telegraph allowed transmission of the

news photograph around the world; cinema introduced

movement into photography; xerography allowed incorporation

of images into the most ordinary newsletter; television

transmitted the image; video allowed it to be recorded,

and the jpg and the avi has brought the photograph and

the moving image to the computer screen.

This famous photograph of a migrant mother during the

dustbowl migrations of the 1930s is an outstanding example

of this sort of photograph. Many of the earliest uses

of photography suggest the power of this inscription

of the actual upon film: pornography etches the nakedness

of an actual model into an image, the portrait captures

a unique individual, and a compiled inventory of mug

shots can aid in the identification of criminals.(T.

Gunning) New technologies extended the reach of the

photograph: the cheap Kodak camera enabled millions

of amateurs to become photographers of the intimate

family life; the telegraph allowed transmission of the

news photograph around the world; cinema introduced

movement into photography; xerography allowed incorporation

of images into the most ordinary newsletter; television

transmitted the image; video allowed it to be recorded,

and the jpg and the avi has brought the photograph and

the moving image to the computer screen.

But with the new forms of digital manipulation of the

image, a breach with the actual has occurred. With the

ability to compose the simulation of a photograph (a

species of "anti-photograph") out of iterable

elements, we may be reaching the close of the era when

a photographic image can be taken as an index of the

actual object, or a moment of inscription. Digial workers

have become to create complex narrative films without

lived actors or material sets: the image is being set

free from the matter it used to etch.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait, 1978. Always

the naughty boy. Note the blatant theatrically and the

arch irony of this image's address to the viewer. With

this image, I find that a website on censorship cannot

elude the dynamics it describes. I have censored this

image, as well as of next five images, in order to respect

the sensibilities of more sensitive viewers.

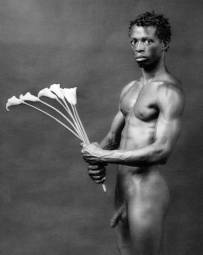

Robert Mapplethorpe and the Contraversy about funding

the NEA: The story of the scandal precipitated by a

showing of a retrosepective show of the photographs

of Robert Mapplethorpe has been told many times. Here

are the key facts: NEA funding was used by the ICA at

Uof Penn to put together a show, entitled "The

Perfect Moment", to offer a retrospective of a

talented young artist Robert Mapplethorpe, who had recently

died of AIDS. The show included provocative images from

gay sexual practices, as well as some images of young

girls with their genitalia exposed. Members of the Christian

right found out about this show, and support for another

photographer Andreas Serrano, which included an image

of a crucifix suspended in urine ("Piss Christ.")

When members of the Christian right circulated some

of these images in their news letters to consituents,

certain members of congress were inundated with protest

letters. This led to a debate on the Senate floor--led

by Jesse Helms and Alphonse D'Amato--condemning the

NEA for sponsoring this pornography as art. The debate

that ensued mobilized the art community, the Christian

right, and many between these two extremes in what came

to called the "culture wars." What is most

pivotal here is the power of photographs to shock--not

simply by what they re-present, but also by what they

evidence--acts and practices and events. These became

the focus of litigation when the director of the Cincinnati

Museum, who had sponsored a show devoted to Robert Mapplethorpe's

photography, was taken to court on grounds of obscenity.

Five photographs were selected as grounds for the prosecution.

Here is one, entitled "Marty and Veronica."

In the most extreme images of the Mapplethrope show--the

X Portfolio--displayed as small images on tables in

the gallery of the show, one could find representation

of sexual practices that were considered by many observes

to go over the line: for many this was not art but pornography--both

improper and inappropriate. Here

are the four other images

entered into evidence at the trail. See if you think

these images are obscene by the Supreme Court standard

in Miller v. California, and then compare your

judgment to the verdict of the jury.

According to Miller vs California (1972) , the

Supreme Court ruled that obscenity was not protected

by the Constitution, and that a work can only be judged

obscene if it meets all three of these tests:

the "average" person finds that it "appeals

to the prurient interest" (by seeking to arouse

sexually); that, applying community standards, the work

depicts or describes sexual conduct in a "patently

offensive way"; the work lacks "serious literatry,

artistic, political, or scientifica value".

In the most extreme images of the Mapplethrope show--the

X Portfolio--displayed as small images on tables in

the gallery of the show, one could find representation

of sexual practices that were considered by many observes

to go over the line: for many this was not art but pornography--both

improper and inappropriate. Here

are the four other images

entered into evidence at the trail. See if you think

these images are obscene by the Supreme Court standard

in Miller v. California, and then compare your

judgment to the verdict of the jury.

According to Miller vs California (1972) , the

Supreme Court ruled that obscenity was not protected

by the Constitution, and that a work can only be judged

obscene if it meets all three of these tests:

the "average" person finds that it "appeals

to the prurient interest" (by seeking to arouse

sexually); that, applying community standards, the work

depicts or describes sexual conduct in a "patently

offensive way"; the work lacks "serious literatry,

artistic, political, or scientifica value".

|

| IV:

Wanting

it My Way in Film and Broadcasting: the demand to be

entertained encounters the imperative to protect young

eyes and ears |

- Movie Production Code 1920

- Invention of Radio and Institution of Broadcast

Networks

- Founding of the FCC -- 1934: 7 forbidden words

- Movie Ratings System 1968: MPA

- Development of Cable Television........allows expanded

programming for TV

- popular adaptation of the VCR

- George Carlan?, Howard Stern and the Affinity Broadcasting

case: 7 forbidden words

- TV rating system -- 1998

- V-Chip introduced in TVs --1999

For most of the last two millennia, the theater has

been the dominant medium of entertainment. Only after

nearly three centuries of print media (1456-1750) did

novel reading emerge as a major form of entertainment.

In the century since the arrival of film, technology

and capital have conspired to expand the power, reach,

and variety of the forms of entertainment: film, radio,

the phonograph, television, video games and the World

Wide Web. Grasping the enormous influence of these new

media, our culture has moved toward a condition of continuous

negotiation between two groups and positions: 1) those

who favor unfettered expression and access: this group

embraces the new entertainment media and claims the

right to produce or consume entertainment texts without

any restraints or filtering, except that exercised by

the consumer of art and entertainment; and 2) those

reformers of media who work to develop systems for controlling

the production, distribution, and access to forms of

mass entertainment, so the impressionable eyes and ears

of the young can be protected from images and ideas

said to menace public morals and community values. Because

of the exuberance of the market forces forever promoting

new forms of enterainment, and because of the absence

of legally sanctioned government censorship, those who

would protect the public against bad media and expose

them to the good, have had to find ingenious new ways

to censor.

Specific episodes in the struggle between expression

and censorship:

- Precursor in Print Media: Novel Reading for Entertainment:

In the late 17th century, authors and booksellers

in Britain developed a brief, easy to read, plot centered

novel that was laced with vivid sex scenes. The popularity

of these novels of amorous intrigue, written by women

writers Aphra Behn, Delariviere Manly and Eliza Haywood,

was a scandal to the more literature traditional book

culture of the day.

Cultural

critics worried that naive young readers would be

absorbed by arousing fictions and emulate their dangerous,

and morally corrupt, life narratives. In response

to new reading practice, Defoe, Richardson and Fielding

wrote novels that absorbed elements of the novels

of amorous intrigue, at the same time that their novels

turned readers toward an ethical mediation upon the

dangers of erotic license and unbridled novel reading.

Subsequent literary history has dubbed these three

canonical authors the originators of the English novel,

and deleted the earlier novels from legitimate literary

history.(Watt) Several factors are crucial to the

elevation of the novel out of a form of entertainment:

novels, as a new literary form, are distinguished

from the popular mass of "mere" fiction;

novels are subjected to "serious" criticism

by reviewing journals; finally, novels are included

in the school curriculum and the object of specialization

by scholars. (W. Warner) This transformation of entertainment

into art takes many years to accomplish: it makes

reading popular fiction a way to pass the time while

novel reading comes to be regarded as an enlightening

cultural activity. Cultural

critics worried that naive young readers would be

absorbed by arousing fictions and emulate their dangerous,

and morally corrupt, life narratives. In response

to new reading practice, Defoe, Richardson and Fielding

wrote novels that absorbed elements of the novels

of amorous intrigue, at the same time that their novels

turned readers toward an ethical mediation upon the

dangers of erotic license and unbridled novel reading.

Subsequent literary history has dubbed these three

canonical authors the originators of the English novel,

and deleted the earlier novels from legitimate literary

history.(Watt) Several factors are crucial to the

elevation of the novel out of a form of entertainment:

novels, as a new literary form, are distinguished

from the popular mass of "mere" fiction;

novels are subjected to "serious" criticism

by reviewing journals; finally, novels are included

in the school curriculum and the object of specialization

by scholars. (W. Warner) This transformation of entertainment

into art takes many years to accomplish: it makes

reading popular fiction a way to pass the time while

novel reading comes to be regarded as an enlightening

cultural activity.

- Censorship and expression in Hollywood: New

technologies produce new and more powerfully absorptive

forms of entertainment, and new rounds of anxiety

about the effects of this new media upon culture.

The development of film brought a remarkable visual

spectacle to all, even the illiterate. Its powers

of verisimilitude opened up the prospect of improving

forms of entertainment. Thus, upon seeing D.W. Griffin's

Birth of a Nation, Woodrow Wilson ascribed

to it nothing less than the power of "writing

history with lightning."(Miller,30) However cultural

critics like Jane Addams, the Chicago social reformer,

took note of the long lines of working people crowding

into the Nicelodeons and suspected the new cinema

of being addictive and debilitating.

Even

the grand moralistic spectacles of Cecil B.

De Mille could include images calculated to arouse

a prurient interest in the audience. With

this shot from The Sign of the Cross, 1932, De

Mille ignored the Production Code's restrictions on

nudity. Notice that while the film represents a Christian

about to become a martyr for her faith, the film fixes

her in a posture and with (a fetching over the shoulder)

glance that suggests her willingness to join in an

erotic embrace with the pagan Satyr figure to whom

she is bound.When

the Catholic Church teamed up with local censorship

boards to take control of the exhibition of the new

cinema, the film industry hired Will Hays, President

Harding's Postoffice master, to organize their own

system of censorship and regulation. In the progressive

narrative usually applied to the evolution of systems

of censorship, the Production Code is usually understood

to be particularly invasive (it worked with studios

at every stage of film production) and proscriptive

(it's offered a long list of "Don't and Be Carefuls"

(Miller, 39-40), while the more benign Rating System

ushered in by Jack Valenti in 1968 is described by

its promoters as a viewer's guide (so parents can

protect children from films not appropriate to their

age) and voluntary (a producer can choose not to have

their film rated). However, in fact, the implementation

of both the Production Code and the Ratings System

have been shaped by several global general features

of the the American film industry. First, the film

industry has no interest in censoring the production

of whatever material can attract viewers (however

sexy or violent), except in so far as self-censorship

is the best way to avoid more draconian forms of federal,

state and local censorship. Secondly, Hollywood censorship

has never been a legal necessity, the failure to receive

the production code seal of approval or a ratings

letter could be so diminish the size of the available

audience that it would have a force equivalent to

law. But finally, whenever a certain system of censorship

reaches equlibrium (naked breasts gets a movie an

"R"), changes in sexual mores and the influence

of foreign imports, can lead to a dissolution of the

earlier concensus. Even

the grand moralistic spectacles of Cecil B.

De Mille could include images calculated to arouse

a prurient interest in the audience. With

this shot from The Sign of the Cross, 1932, De

Mille ignored the Production Code's restrictions on

nudity. Notice that while the film represents a Christian

about to become a martyr for her faith, the film fixes

her in a posture and with (a fetching over the shoulder)

glance that suggests her willingness to join in an

erotic embrace with the pagan Satyr figure to whom

she is bound.When

the Catholic Church teamed up with local censorship

boards to take control of the exhibition of the new

cinema, the film industry hired Will Hays, President

Harding's Postoffice master, to organize their own

system of censorship and regulation. In the progressive

narrative usually applied to the evolution of systems

of censorship, the Production Code is usually understood

to be particularly invasive (it worked with studios

at every stage of film production) and proscriptive

(it's offered a long list of "Don't and Be Carefuls"

(Miller, 39-40), while the more benign Rating System

ushered in by Jack Valenti in 1968 is described by

its promoters as a viewer's guide (so parents can

protect children from films not appropriate to their

age) and voluntary (a producer can choose not to have

their film rated). However, in fact, the implementation

of both the Production Code and the Ratings System

have been shaped by several global general features

of the the American film industry. First, the film

industry has no interest in censoring the production

of whatever material can attract viewers (however

sexy or violent), except in so far as self-censorship

is the best way to avoid more draconian forms of federal,

state and local censorship. Secondly, Hollywood censorship

has never been a legal necessity, the failure to receive

the production code seal of approval or a ratings

letter could be so diminish the size of the available

audience that it would have a force equivalent to

law. But finally, whenever a certain system of censorship

reaches equlibrium (naked breasts gets a movie an

"R"), changes in sexual mores and the influence

of foreign imports, can lead to a dissolution of the

earlier concensus.

- Free radio broadcasting for entertainment:

Early radio was developed as a wireless extension

of the telegraph and the telephone enabling point

to point confidential communication in places where

wires were impractical, for example between two ships

at sea during battle. The development of radio broadcasting

as a means of "instantaneous collective communications"

was unexpected by early radio visionaries and almost

accidental (Czitrom, 71). Only over the course of

the decade after WWI does radio broadcasting achieve

the media primacy it was to enjoy before the advent

of television in the late 1940s. Early on in the history

of radio broadcasting, it was widely recognized that

the unprecedented communicative power of live radio

broadcasting required strict restraints upon expression:

otherwise, what was to protect a child or adolescent,

innocently scanning the airwaves in the privacy of

their own home, from being subjected to the errant

tongue of a radio announcer. In order to understand

the highly circumscribed interplay between censorship

and expression in this new medium, it is important

to grasp those elements of the American institutionalization

of radio broadcasting that assured its essentially

commercial telos:

a) An advertising agency receives money from a company

(hereafter a "sponsor") develops or buys

radio entertainment (hereafter the "show")

as a vehicle for its advertisement, and rents broadcast

time from a station or group of stations (hereafter

the "network"). b) The broadcast station

licenses a particular bandwidth for transmission from

the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which

acts as a traffic cop preventing different transmittors

from deforming each other's signals, but is quite

explicitly discouraged from any active supervisory

control over the content broadcast over the radio

system. c) The radio audience is structured as a group

of autonomous consumers who may choose to buy a high

tech radio receiver and can then turn the dial to

whatever free "show" he or she enjoys. Notice

how the power to speak and censor have been distributed

within this system. Because the advertising agency

assumes the crucial medial role of translating the

money of the sponsor into the ads and shows it pays

the stations to broadcast, advertising's speech is

primary and formative. In keeping with a longstanding

American suspicion of the state, the federal government

has no direct speech on radio. However, through the

FCC, it guards the airwaves for

those who can make money from them, and holds an ultimate

power (by refusing to renew a radio license) to silence

those who might use the new medium in ways it deems

subversive or distasteful. The new mass audience of

radio broadcasting has no powers of speech on radio;

it only has the limited and negative option not

to buy a radio or not to tune in a station.

In such a system, censorship is indirect, and usually

invisible: it consists of all those ideas and messages

the controllers of the commercial medium declines

to speak, or allow be spoken, because they might offend

the taste or sour the mood of a significant number

of the consuming audience. In the "golden age"

of the 30s and 40s, the commercial structure of network

radio allows it to be a self-censoring vehicle for

building consent. The commercial telos of the broadcast

networks helps explain the odd phenomena Europeans

noticed much later in the 1960s, during the Vietnam

War. While the European press carried highly critical

accounts of American conduct in the war, US television

reported the war in Vietnam in terms so close to the

official government line, that independent observers

noted this paradox: the representation of the war

by a "free" press was the functional equivalent

of censorship.

- The decay of network television: The successful

transfer of the radio network system to television

in the late 1940s worked to consolidate the new medium

of television as the dominant provider of entertainment

and news. More than ever a large segment of public

culture--from political critique to experiemental

film--found itself outside of the nation's dominant

medium, television. Many decried the monopoly controlled

by the three networks in the US; Newton Minow, Kennedy's

appointment as chairman of the FCC sought to shake

things up by characterizing television as a "vast

wasteland." Foundations (like the Ford Foundation)

sought to raise the quality of television by supporting

the development of educational television and publicly

funded televsion. But from the vantage point of the

present, we can see that a succession of mutations

in television technology and practice have eroded

central control enjoyed thoughout the 1950s and 1960s

by the networks:

- The use by the network of video tape to record and

replay television shows (begun in 195?) took television

away from the live "real time" performance

characteristic of theater and live radio toward becoming

a medium that could be archived, replayed, and moved

to commercial tape.

- The remote control, by allowing viewers to channel

surf, mute and zap, won them greater control over

shows, ads and the network programing strategies.

- The VCR offered further freedom from the network

schedule, but more importantly, it also opened the

home to a broad spectrum of film entertainment, much

of it too violent or sexually explicit to be broadcast

on network television.

- The coming of cable produced a de facto loosening

of television censorship: it allows programming for

narrower segments of the audience (e.g. teens were

taught to say "I want my MTV"); although

the initial bribe--free television programming in

exchange for a commercially mediated, ad interleaved

entertainment--was withdrawn for increasing numbers

of viewers, the simple fact that one pays for cable

TV, transfers additional responsibility for that act

of consumption from the network programmer to the

viewer.

- Yet, in the age of the proliferation of sets, and

increasingly lax supervision of children by their

parents, those who would censor have won a new ratings

systems for television, to be used in tandem with

a V-chip placed in every set. This new censorship

of television screen, by labelling content and opening

the set to a parent's remote control of viewing, functions

as a filter of content. It is America's latest compromise

between the central commercial imperative (maximum

access by the media industries to American homes;

maximum choice by consumers), and American values:

the privileging of freedom of

speech and a viseral distaste for regimes of censorship.

Factors disrupting and reforming modern systems

of media censorship: From the critical elevation

of the novel to the introduction of the V-chip, these

systems of censorship unfold within entertainment systems

sustained by the market and in the absence of official

government censorship. If one looks at specific episodes

in this ongoing negotitiaton, one finds that those favoring

unfettered access receive support from several factors:

the Anglo-American relectance to censor; the profit

motive, which pushes producers to increasingly extreme

forms of sex, sin and violence; and, successive mutations

in the technologies that reproduce and disseminate entertainment.

However, ironically, these same factors--the absence

of direct censorship, the centrailty of the market,

and technological innovation--have instigated new techniques

for censorsing mass entertainment. |

| V: Censorship and Speech

on the Web

|

- Founding of the WWW - 1994

- Communications Decency Act 1996

- Overturning of CDA - 1997

- Pamela Anderson/ Tommy Lee Curtis porn video --1998

- Starr Report is released on the Web by the House

of Representatives -- Fall, 1998

- Civil suit in Portland Oregon leads to $109 million

dollar fine for the "Nuremberg Files" web

site leading to its removal from the Web

Each of the components of this web essay offers ways

to understand why the arrival of the World Wide Web

has brought speech and censorship into collision. Like

the onset of print in the early modern period, the Web

has changed the medium within which knowledge work is

conducted and stimulated an expansion of the numbers

and varieties of the centers of production. These changes

in the medium and quantity of communication have changed

the quality of media culture and disrupted the ratio

of speech and censorship within the prevailing media

ecology. At the same time, the arrival of the Web has

expanded the powers of speech and reinvigorated the

ideals of public culture. Perhaps, as some commentators

have written, the Web will make good on the largely

unrealized promises made earlier in the 20th century

on behalf of radio and television, by enabling unprecedented

political participation by the average citizen. But

the very features that cause Web evangelists and libertarians

to enthuse--the power of one producer to broadcast to

millions of linked computers without the supervision

of any single agency of control--have caused others

to call for new systems of censorship. To understand

why one must take note of two features of the Web.

- The Web traces its origins to the first Internet,

ARPAnet--a network that was radically centerless by

design: the Internet is not one network, but a network

of networks "designed to be a decentralized,

self-maintaining series of rudundant links between

computers and computer networks, capable of rapidly

transmitting communications without direct human involvement

or control." (ACLS v Reno; District Apellate

Court Panel Decision, June 12, 1996, "Findings

of Fact; "the nature of Cyberspace") This

structure was devised during the Cold War to insure

survivability in case of nuclear attack. But this

also means that communication over the the Internet

(unlike the Postal Service or Telecommunications)

is not supervised by any one government agency, company,

or group of companies. It is decentralized by design,

has become thoroughly international, and moves information

at speeds that make control or supervision from a

single site exceedingly difficult to envision. For

this reason the Cold War may have spawned a distributed

communications network so resistant to central control

that there is no real way to stop a determined and

financially independent "speaker" of pornography

or hate speech. Now the absence of any central node

of control has this unintended consequence: WWW may

be censorship-proof. And this especially troubles

those that want to inflect this new digital medium

so that it reflects--in its structure and contents--even

the most minimal common social values.

- The Internet comes to the Market: As long as the

Internet was a way for military labs, universities,

and then corporations to share their advanced research,

it operated free of the market and its imperatives.

But once an easy to use graphical interface was invented

(with HTML and the protocols it requires), the WWW

has become the focal point for frenetic commercial

activity. One of the first commercial uses of the

Web was the sale of pornography. There were several

factors that made the WWW has become especially accommodating

venue for porn: 1) by drawing upon two existing networks--the

phone network and the credit card network--Web based

pornography could allow private "viewing"

by a relatively anonymous consumer; 2) because the

Web is a digital network, it can translate analogue

forms--still photographs, video, and audio--onto Web

sites, and with the improvement in browser and server

software, it is doing so at increasing powers of resolution.

3) At the same time that the market has made the Internet

rich in resources, the international scope of the

Web has freed it from most of the contraints of local

and national law. The way the Web has unsettled the

boundary between private and public life, and challenged

the role of traditional media gate keepers, is apparent

in two recent episodes. When the Starr Report was

posted to the Web, it offered an uncensored account

of the most intimate details of President Clinton's

affair with Monica Lowinski. The fact that it was

"already out there" on the Web meant that

many newspapers around the country felt impelled to

desist from the sort of censorship they might otherwise

have practiced. Secondly, when a private video tape,

made by Pamela Anderson (of Bay Watch) and Tommy Lee

Curtis (of Men in Black) to record their sex acts

on one Halloween night, became posted on innumerable

porn web sites for viewing by millions.

Worries about the access by minors to Web porn, and

unwonted solicitation in chat rooms and through email,

led Congress to pass the Communications Decency Act

(Title V of the Telecommunications Act of 1996). It

was a failed first attempt to place limitations upon

this powerful new medium. There were three provisions

of this bill that became the focus of the successful

appeal by the ACLU to the United States District Count

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and subsequently,

the Supreme Court. One section of the bill provides

in part that any person who, "by means of a telecommunications

device" "knowingly...makes, creates or solicits"

and "initiates the transmission" of "any

comment, request, suggestion, proposal, image or other

commuication which is obscene or indecent, knowing that

the recipient of the communication is under 18 years

of age," "shall be criminally fined or imprisoned."

Note: this law does not just punish what is already

illegal--obscenity and child pornography. It also punishes

"indecent" communication, a much vaguer and

broader category of speech. In order to define "indecent"

speech, a second section of the bill defines the patently

offensive as "any comment, request, suggestion,

proposal, image, or other communication that, in context,

depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as

mearused by contemporary community standards, sexual

or excretory activities or organs,..." Finally,

the law makes it a crime for anyone to "knowingly

permit any telecommunications facility under [his or

her] control to be used for any activity prohibited"

in the first two of these sections. Among the many objections

voiced to the CDA, three arguments were most decisive:

1) By extending the legal framework traditionally applied

to radio and television, instead of the legal precedents

developed for print publication or telephone communcations,

Congress was miscontruing the nature and potential of

the Internet. 2) By seeking to criminalize expression

that was "indecent" or "patently offensive"

they were passing an unconstitutionally vague restriction

of freedom of expression; it could, for example, make

non-obscene but "explicit" speakers about

sex--artists, scientists, providers of information about

AIDs--libel to criminal prosecution. The only way to

protect oneself from a statute that is vague and overbroad

is through silence. 3) Finally, by making most of the

parties to Internet communication--from content providers

to internet prividers to a host of private and public

institutions--legally libel for speech that someone

under the age of 18 might "hear," the Communications

Decency Act underestimates the difficulty of controlling

access and use of the network from the point of production

or distribution. Therefore, such legislation would have

a chilling effect upon all speech on the Internet. In

the most quoted sentences of the Philadelphia Federal

Appeals Court judgment, the Court applied the First

Amendment valorization of freedom of speech as a exchange

that is valuable because it is openended: "Cutting

through the acronyms and argot that littered the hearing

testimony, the Internet may failry be regarded as a

never-ending worldwide conversation. The Government

may not, through the CDA, interrupt that conversation.

As the most participatory form of mass speech yet developed,

the Internet deserves the highest protection from governmental

intrustion." (http://www.eff.org/pub/Censorship/Internet_censorship_bill.../960612_aclu_v_reno_decision.htm)

The overturning of the CDA was widely viewed at a victory

for freedom of speech on the Internet. But troubling

implications of the Internet's amplification of the

power of speech is suggested by two other episodes.

An anti-abortion group developed a site entitled the

Nurenberg Files. The web site title, by referring to

the site of post WWII war crimes trials in the German

city of Nurenberg, suggests what the site makes explicit:

the analogy between abortionists and Nazi war crimes.

The site is laced with vivid photographs of aborted

fetuses. But its most inflammatory element is a list

of doctors, nurses and other health professionals working

in abortion clinics around the country--complete with

names, addresses, phone numbers and photographs--with

those who have been murdered crossed out, those who

have been injured, with typeface in red. Is this free

speech or a hit list? A court found that the site had

qualities of a hit list and was inciting its viewers

to violence. Therefore a legal injunction or restraining

order was won against this site and it was closed down.

(check) How can one stop the use of internet speech,

and the forging of internet communities, around acts

and causes most responsible members of the body politic

would find deplorable? In the wake of Buford's attack

upon a Los Angeles Jewish community, an act he described

as a "wake up call to Americans to start killing

Jews" (check), a New York Times article focused

upon the problem of stopping acts of domestic terror

by a "lone wolf" who, because he acts alone,

is practically immune from advanced detection (NYTimes,

8/16/99). In considering the origins of this relatively

new form of terrorism, the article argued that the speech

of hate groups receives technological amplification

from the Internet. Here the most celebrated qualities

of the Web--its ability to forge community through participation

by many; the ability to enable affiliation around a

salient issue across great distances--becomes the source

of danger to the society as a whole. "Terrorism

experts point out that advanced in technology, in particular

the Internet, have fueled the activities of loners,

making it easy for them to communicate and gain access

to extremist philosophers. 'It puts them all in the

loop,' said Rabbi Marvin Hier, Dean and Founder of the

Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, which monitors

2,100 hate sites on the Web. 'They feel linked up. They're

not alone. It makes them part of a greater thing. it's

ther ticket to the world.'"

Because some form of censorship and constraints enable

speech, it is not a question of whether but how we will

find ways to "censor" Internet speech. Because

the Web is becoming an increasingly commercial medium,

the question of copyright and fair use looms large.

Economic censorship--censorship on the grounds of copyright--seems

to be emerging as the most formidable form of censorship.

|

First composed in 1998

overview

| schedule | assignments | links

| student projects | UCSB

English | Transcriptions

LCI

|