Interfacing Knowledge: New Paradigms for Computing in the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences

March 8-10 2002, University of California Santa Barbara

Perfect Transmissions: Evil Bert Laden

Mark Poster

Film Studies and History, UC/Irvine

(all

rights reserved)

In the globally networked world, strange, unexpected

and sometimes amusing events occur. I shall analyze one such happening with the

purpose of understanding how the global communication system affects national

cultures. It is my hypothesis that the current state of globalization, of which

the Internet is a major component, imposes a new and heightened level of

interaction between cultures. This interactivity changes each culture in many

ways, one of which I highlight: the degree of autonomy of each culture is

significantly reduced as a consequence of the global information network. On

the one hand, all attempts to sustain such autonomy tend to become retrograde

and dangerous. Local beliefs, values,

and practices can no longer be held as absolute or as exclusive, at the expense

of others. On the other hand, a new opportunity arises for a practical

definition and articulation of global, human or better posthuman culture. In

short, henceforth, the local is relative and the global may become universal. This

universal, unlike earlier attempts to define it or impose it, will be

differential, will consist of a heterogeneity of glocal fragments.

Although there are significant

economic and demographic components of the new level of global interactivity, I

address the issue of the flow of cultural objects within cyberspace. New media

contribute greatly to the quantity and quality of the planetary transmission of

cultural objects. Cultural objects – texts, sounds and images – posted to the

Internet exist in a digital domain that is everywhere at once. These objects

are disembedded from their point of origin or production, entering immediately

into a space that has no particular territorial inscription. As a result, the

Internet constitutes distributed culture, a heteroglossia that is commensurate

with the earth. Cultural objects in new media are thus disjunct from their

society. They are intelligible only through the medium in which they subsist.

Cultural objects in cyberspace elicit a new hermeneutic, one that underscores

the agency of the media, rendering defunct figures of the subject from all

societies in which it persists and persisted in a position separate from

objects.

For the Internet enables planetary transmissions of

cultural objects (text, images and sound) to cross cultural boundaries with

little “noise.” Communications now transpire with digital accuracy. The dream

of the communications engineer is realized as information flows without

interference from any point on the earth to any other point or points.

Cybernetic theory is fulfilled: both machines and the human body act on the

environment through “the accurate reproduction” of information or signals, in

an endless feedback loop that adjusts for changes and unexpected events. (Wiener) And yet, as Derrida argues in Postcard things are not so simple. (Derrida) All the bits and bytes are there alright but the

message does not always come across or get decoded. Misunderstandings abound in

our new global culture, sometimes in quite pointed ways. This article is about

one such miscommunication. It concerns a perfect transmission of an image half

way around the globe that somehow went awry. Indeed one may argue that the

global network, with its instantaneous, exact communications, produces

systematically the effect of misrecognition as information objects are

transported across cultural boundaries. Global communications, one might say,

signifies transcultural confusion. At the same, the network creates conditions

of intercultural exchange that render politically noxious any culture which

cannot decode the messages of others, which insists that only its transmissions

have meaning or are significant. As never before, we must begin to interpret

culture as a multiple cacophonies of inscribed meanings as each cultural object

moves between cultural differences. Let us look at one instance of the issue

that I have in mind.

The second week of October 2001 was

eventful with the onset of U.S. and British bombing in Afghanistan. Like many

Americans I listened intently to reports of the war and to analyses by informed

commentators and academics. On Friday of that week, a few days after the start

of the bombing, I heard, on a National Public Radio broadcast, one expert on

Middle Eastern cultures explain to the interviewer and audience that among the

many aspects of American society that antagonize Islamic fundamentalists the

worst is American popular culture. Even more than American support for Israel

or the American led embargo of Iraq, the enemy, in the eyes of these Muslims,

is, of all things, American popular culture. With some surprise, I filed this

bit of knowledge somewhere in my brain’s database and continued my ride home.

Much could be said about American popular culture in the

age of what Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri call “the Empire.” (Hardt and Negri) Here I need only note that a

peculiarity of many Americans is the emotional fixation they often develop for

figures in popular culture, not simply for acknowledged celebrities but for all

manner of objects: clothing, food, animated figures, music, television shows,

and so forth. Americans obsess about selected aspects of popular culture. One

such American is Dino Ignacio who had an extraordinary dislike for Bert, a

muppet on public television’s longstanding children’s show, Sesame Street. For Mr. Ignacio, Bert was

evil. To satisfy his obsession, Ignacio created a Web page entitled “Bert is

Evil.” Here with the aid of a Web browser one finds Ignacio’s “evidence” of the

muppet’s alleged misdeeds. Among this evidence is a series of images that

Ignacio thinks prove the point: Bert is pictured with Hitler, with the KKK,

with Osama bin Laden, [see Figure 1] and with a long list of other evil-doers.

. Figure 1: Bert

& Osama from Evil Bert Web Page

Figure 1: Bert

& Osama from Evil Bert Web Page

Bert’s

crimes are thus detailed with fastidious and unrelenting hostile energy.[1]

Perhaps Ignacio has too much time on his hands but in any case his Web design

is characteristic of the commitment of many Americans to their peculiar,

fetishistic attachments to popular culture figures. An understanding of this

aspect of popular culture in the United States is essential to appreciate what

follows.

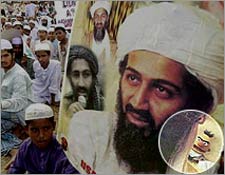

On

Sunday, October 14th, a friend emailed me with an urgent message to

look at the New York Times for an

incredible story about a protest in Bangladesh on October 8th

against American bombing in Afghanistan. The story he referred to by Amy

Harmon, one of my favorite journalists writing on new media, included a picture

of the protestors in Bangladesh carrying a poster of bin Laden that was an

attractive collage composed of several images of him along with a tiny picture

of Bert the Sesame Street muppet

sitting on his left shoulder and staring smugly. [Figure 2]

Figure 2:

Image from NY Times Article

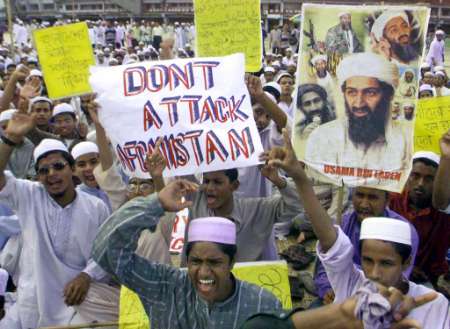

Another photograph that I found on

the Web indicates more clearly the face of

evil Bert. [see Figure 3]

Figure 3: Bert is Highlighted

Bert is in the highlighted circle, grimacing

at the viewer more fiercely than Osama. How was it possible for Bert to get

into the scene in Bangladesh? Amy Harmon could not explain the inclusion of Bert

in the poster but there he was for all the world, and especially protesting

Islamic militants, to see. Perhaps he truly was evil, living up to Ignacio’s

image of him, siding with the Al Qaeda terrorists.

Bert is in the highlighted circle, grimacing

at the viewer more fiercely than Osama. How was it possible for Bert to get

into the scene in Bangladesh? Amy Harmon could not explain the inclusion of Bert

in the poster but there he was for all the world, and especially protesting

Islamic militants, to see. Perhaps he truly was evil, living up to Ignacio’s

image of him, siding with the Al Qaeda terrorists.

I was fascinated by Harmon’s story

and the accompanying photograph. Out of curiosity I searched the Web for more

information about Bert’s remarkable presence in Bangladesh. A simple image

search for “evil Bert” in Google yielded the following photographs [see Figures

4-7] that confirm the one reproduced in the New

York Times’ article. They are also significant to understand more of the

story.

Figure 4: Photo from Protest in Bangladesh

Figure 5: Another Photograph

Figure 6: A Longer Shot Showing English Banner

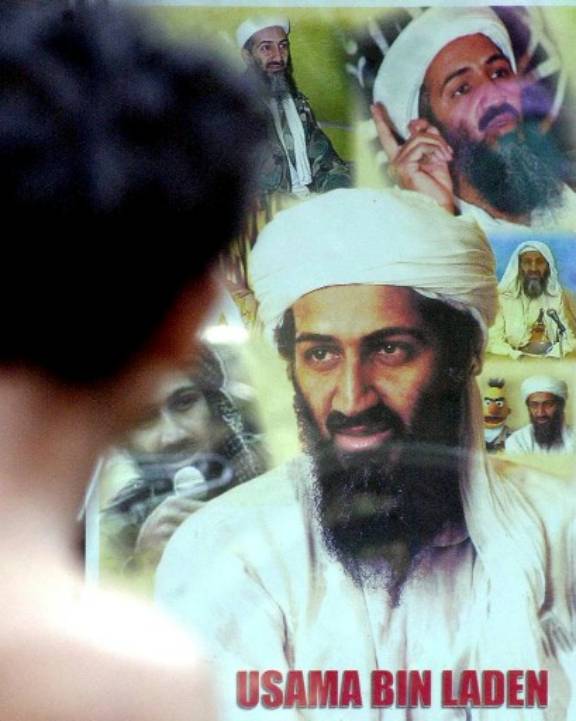

Figure 7: Poster Indicates Evil Bert Image in Collage

This

last photograph [see Figure 7] yields the best information about how evil Bert

managed to appear in the poster. It shows that the image of Bert in the poster

is taken from Ignacio’s web page. The image on the Evil Bert page has simply

been set into a collage of images of Bin Laden. There are eight images of Bin

Laden in the poster, including one from the Evil Bert page. In fact the image

of Bin Laden that Ignacio combined with one of Bert is the same one that is

positioned centrally in the poster.

When I began to relate the story of

Bert’s appearance in a pro-Taliban demonstration to colleagues and students at

UCI, I encountered another strange twist: about half the people to whom I

showed the New York Times story and

photo concluded that it indicated a sophisticated knowledge of American pop

culture by the Bangladesh militants. They appropriated, as cultural studies

scholars would say, the nasty image of Bert and shoved it into the face of

Westerners as if to say, if you think Osama is evil, we’ll take evil Bert on

our side and use him against you. Another 25% of my respondents simply did not

believe the photo at all. In the age of digital images, they surmised the photo

was doctored: someone in the West had added the figure of Bert to the photo

that appeared in the New York Times.

Evil Bert, they concluded, never appeared in the protest in Bangladesh. The

rest of my respondents accepted the image at face value and were utterly at sea

to explain it.

I next went online again to pursue

the discussion. I found a flurry of comments about the photo. Some Scandinavian

newspapers were convinced it was a hoax.[2]

Others assumed the protesters in Bangladesh, unlike their Taliban compatriots,

watched American television and were avid Sesame

Street fans. The photo produced a variety of misunderstandings by

Westerners of Bangladesh culture. The Babel-like confusion of cultural tongues

only heightened with the transmission of more and more information from across

the globe.

Meanwhile Mr. Ignacio must not be

left out of the picture, so to speak. For he also became a victim of

information overload. His reaction to the New

York Times story was guilt. He very quickly took down the Evil Bert Web

page and posted in its place an apology. He concluded that somehow his Web page

abetted terrorism. On his “apology” Web site he stated his remorse, admitting

that “reality” had intruded into his fantasy. In his words, “…this has gotten

too close to reality…” (Ignacio) Suddenly his obsession with Bert decathected and left

him, shorn of his libidinal outlets, staring fixedly at his own super-ego

induced guilt. With a global audience presumably shocked and angered at his Web

design, Ignacio now suffered from the burst bubble of his fetish.

But that was not the end of his

woes. The Internet does not forget so easily the “crimes” of its producers.

What Ignacio wanted to hide would not disappear. For other Web authors,

admiring his work, created mirror sites. Indeed at least nine of them were up

and running at one point shortly after October 14th, all displaying

boldly the full variety of Evil Bert’s deeds and photographic evidence for

them, including the controversial image of Bert with Osama bin Laden. The

emergence of the mirror sites complicates the cultural confusion, subverting

the power of authors to control their work in yet another manner. Not only did

the anti-American militants of Bangladesh unknowingly and without authorization

appropriate Evil Bert, but other Americans, admiring the handicraft of Ignacio,

perpetuated his work for their own ends.

For their part, the producers of Sesame Street were also not amused by

the perfect transmission of the image of Bert. They are quoted in a CNN report

with the following response to the event: “Sesame

Street has always stood for mutual respect and understanding. We’re

outraged that our characters would be used in this unfortunate and distasteful

manner. This is not humorous.”(CNN)

How did the image get on that poster

in Bangladesh? The answer is simpler in one sense and more complex in another

than the views and imaginings of my respondents, as I reported above. A

journalist discovered finally who made the poster, telephoned the company, and

unraveled at least part of the mystery. A local graphics company in Bangladesh

was hired by the militants to produce a poster for the demonstration. It had to

be done quickly because the protest was planned for the day after the bombing

commenced in Afghanistan. In these

circumstances, the company did what anyone today would do. They went on the

Web, did an image search for Osama bin Laden, and presto, downloaded a number

of them, including, we must note, the image from the Evil Bert Web page. They

also put out a request to friends who emailed images to them as attachments.

The representative of the graphics company admitted outright that the employees

did not notice Bert when they put together several images of bin Laden for the

poster. Here, incredible as it might seem to some, is the report on the Urban

Legends Web page: “Mostafa Kamal, the production manager of Azad Products, the

Dhaka shop that made the posters, told the AP he had gotten the images off the

Internet. `We did not give the pictures a second look or realize what they

signified until you pointed it out to us,’ he said.”(Mikkelson and Mikkelson) It was as simple as that: the transmission of Bert’s

image went completely unnoticed in the culture of Bangladesh. Invisibly to the

militants of Bangladesh, Bert snuck into the poster where he was indeed noticed

by Western journalists covering the story of the protest.

It could be that the poster company

representative lied to the Western journalist, perhaps not wanting to take

responsibility for the inclusion of Bert in the poster. Perhaps the company

representative did not have accurate information about the image of Bert.

Perhaps the company intentionally put Bert in the poster as a joke or as an

ironic comment either to the West or to the protesters. Even if any of these possibilities were

true, the fact remains that the protestors themselves appear not to have

noticed the image of Bert and are certainly not likely to recognize his image

from the Sesame Street program. The

photos of the demonstration indeed show some banners in English. Even the

notorious photo in the New York Times

has a caption with bin Laden’s name in Roman alphabet. At least some of the

demonstrators were aware of Western media coverage of the event and were

interested in getting a message to the West about who they supported and what

they wanted to happen.[3]

Nonetheless the circuit of

transmission was closed. We may conclude that in all likelihood the protestors

in Bangladesh did not see the image of Bert. From Ignacio’s anti-cult Web site

to the anti-American pop culture protest half way around the world, and back

again to the West in the medium of print journalism, evil Bert’s digital bytes

circumnavigated the globe in a series of misrecognitions, perfect

transmissions, confusions, blends of politics and culture that surely speaks

much of our current global culture.

The conditions of global cultural

transmissions in the case of Bert Laden initiate many changes in communications

practices in all societies. The Internet imposes everywhere new challenges and

offers new opportunities. The political consequences of the response to the

Internet are serious indeed. Just as the mixing of peoples within a nation

renders especially noxious parochial ethnic and racial attitudes, so the mixing

of cultural objects in the Internet compels each culture to acknowledge the

validity, if not the moral value, of such objects that may be alien and other.

With Bert Laden, the stakes are especially high in the context of the war

between Al Qaeda and the American led coalition.

Mass communications scholars tell us that the failure

of recognition of Bert by the Bangladesh protesters is a case of “aberrant

decoding.” (Fiske and Hartley, p. 81) They failed to interpret correctly the image of Bert

and Osama. This omission was however highly motivated. The protesters cherished

a pre-existing hostility toward American popular culture, even though they

inadvertently displayed one of its minor icons in their demonstration. Their

hostility to U.S. popular culture, like that of other fundamentalist Islamic

groups, derives from a wish to maintain the autochthony of their own beliefs

and values. They wish to insulate themselves against American popular culture,

viewing it as a potent threat to their own way of life perhaps in part because

of its popularity with other Muslims or Middle Easterners. Yet exactly this

effort at insulation proved impossible in the instance at hand.

In another example of parochial attitudes, a highly

respected Middle Eastern journalist, Ali Asadullah, reported in an Islamic

online newspaper about the problem with American and in this case Western

culture. In an article entitled “Spice Girls: Exactly the Reason Why Bin Laden

Hates the West,”(Asadullah) Asadullah reported that a former Spice Girl, Geri

Haliwell, on October 6th, one day before the bombing began in

Afghanistan, entertained British Troops in Oman. For this respected Muslim

journalist, that was all the proof needed to explain, and indeed to justify,

disdain by some of Islamic faith for U.S. and British society. “…the core

causes for terrorist rage and aggression against the United States,” he wrote,

was “the Spice Girls,” not “hatred of freedom, liberty and democracy…” Muslims,

he continued, “want their cultures, traditions and religious and societal

standards to be respected.”

I argue this is exactly the logic that no longer

works. With globally networked digital communications, one must be especially

careful in taking as an offence the legitimate cultural practices of another

even if they are on one’s soil. I will not make any invidious comparisons of

the practices of the Taliban with regard to women to those of the British, but

you can imagine easily where my sentiments lie given my cultural context. Because

cultural objects circulate everywhere, there is no longer any local soil on the earth. Moral outrage

directed at the cultural practices of others, especially toward those that do

no physical harm, today becomes particularly obnoxious. Journalists and intellectuals

such as Asadullah, with his smug air of moral repugnance at Western popular

culture, do much harm in justifying the sentiments from which arose the hideous

murders of September 11th.

What is more, the luxury of such a moral claim,

inspired in this and many other cases not by any means limited to the world of

Islam, is often grounded in versions of monotheism. It may be that in the

present context the collective human intelligence embodied in the Internet is

set in a deep cultural opposition to parochialism in general and to versions of

monotheism in particular that refuse the condition of cultural pluralism. The

one and only God will have to make way for many one and only Gods. If that is

the case, then the Bert Laden incident is more than an amusing series of

cross-cultural confusions but an allegory of changes in contemporary culture,

conditions rife with profound political implications.

The main interest of my intervention is not, however,

to renew a theological critique. Rather my purpose is to raise the questions of

the general role of media in culture and the particular role of new media.

Transmission may now, in the digital domain, be both noiseless and incoherent. Interpretive practices

must accordingly recalibrate themselves to the conditions of planetary culture.

Research about any cultural object in cyberspace entails an infinite series of

interpretive acts. Translation is now a central dimension of any cultural

study. Texts, images, and sounds now travel at the speed of electrons and may

be altered at any point along their course. They are as fluid as water and

simultaneously present everywhere. They mock the presuppositions of all

previous hermeneutics and the subject positions associated with them. They

require a discipline of study unlike any that has subsisted in academic

institutions. From this vantage point, Evil Burt, the emblem I have selected to

designate cyber-culture, is indeed a trouble-maker.

References:

Asadullah, Ali. Spice Girls: Exactly the Reason Why Bin Laden Hates

the West. October 9, 2001 2001. Available: http://www.islamonline.net/English/ArtCulture/2001/10/article4.shtml.

December 10 2001.

CNN. 'Muppet' Producers Miffed over

Bert-Bin Laden Image. October 11, 2001 2001. Available: http://www.cnn.com/2001/US/10/11/muppets.bindladen/.

December 10 2001.

Derrida, Jacques. The Post Card : From

Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Fiske, John, and John Hartley. Reading

Television. London: Methuen, 1978.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Empire.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Ignacio, Dino. Good Bye Bert. 2001.

Available: http://www.fractalcow.com/bert/bert.htm.

December 10 2001.

Mikkelson, Barbara, and David Mikkelson. Bert

Is Evil! October 12, 2001 2001. Urban Legends Reference Pages. Available: http://www.snopes.com/rumors/bert.htm.

December 10 2001.

Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human

Beings: Cybernetics and Society. New York: Doubleday, 1950.