The Pamela Media Event |

|

Appendix:

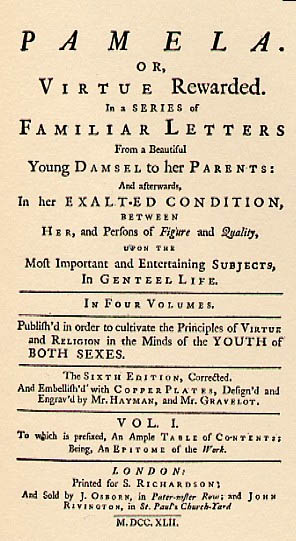

Chronology of the Pamela media event Note: The story of the unprecedented

response to Pamela has been frequently told—from Titles and dates of the key

texts of the Pamela media event: May,

1741: Pamela 4th edition Sept,

1741: Vol. 2 of Kelly’s Pamela’s Conduct in High Life Oct.,

1741: Pamela 5th edition Nov.

1741: Charles Povey’s The Virgin in Sept.,

1742: Pamela in High Life continues where Vol. 1 of Kelly had

stopped 1742:

The Virtuous Orphan: or, the Life of Marianne. Anonymous translation

of Marivaux, "improved in its moral sensibility." 1743:

March 28: Joseph Andrews 3rd edition (3,000 copies) |

The Problem of Visualization

Pamela,

1740 He by Force kissed my Neck and Lips; and said, Who ever blamed Lucretia, but the Ravisher

only? and I am content to take all the Blame

upon me; as I have already borne too great a Share for what I have deserv'd.

May I, said I, Lucretia

like, justify myself with my Death, if I am used barbarously? O my good

Girl! said he, tauntingly, you are well read, I see; and we shall

make out between us, before we have done, a pretty Story in Romance,

I warrant ye! He then put his Hand in my Bosom, and the Indignation

gave me double Strength, and I got loose from him, by a sudden Spring,

and ran out of the Room; and the next Chamber being open, I made shift

to get into it, and threw-to the Door, and the Key being on the Inside,

it locked; but he follow'd me so close, he

got hold of my Gown, and tore a Piece off, which hung without the Door.

I just remember I got into the Room; for I knew nothing

further of the Matter till afterwards; for I fell into a Fit with my

Fright and Terror, and there I lay, till he, as I suppose, looking through the Keyhole, spy'd

me lying all along upon the Floor, stretch'd

out at my Length; and then he call'd Mrs.

Jervis to me, who, by his Assistance, bursting

open the Door, he went away, seeing me coming to myself; and bid her

say nothing of the Matter, if she was wise. Poor

Mrs. Jervis thought it was

worse,…(Pamela, Oxford World Classic, 32) Pamela

Censured,

Was not the Squire very modest to withdraw? For she

lay in such a pretty posture that Mrs. Jervis thought it was worse,

and Mrs. Jervis was a woman of discernment; … The young lady by thus

discovering a few latent charms, as the snowy complexion of her limbs,

and the beautiful symmetry and proportion which a girl of about fifteen

or sixteen must be supposed to show by tumbling backwards, after being

put in a flurry by her lover, and agitated to a great degree, takes

her smelling bottle, has her laces cut, and all the pretty little necessary

things that the most luscious and warm description can paint, or the

fondest imagination conceive. How artfully has the author introduced

an image which no youth can read without emotion! The idea of peeping

through a keyhole to see a fine woman extended on the floor, in a posture

that must naturally excite passions of desire, may indeed be read by

one in his grand climacteric without ever wishing to see one in the

same situation, but the editor of Pamela directs himself to the

youth of both sexes; therefore all the instruction they can possibly

receive from this passage, is, first, to the young men that the more

they endeavor to find out the hidden beauties of their mistresses, the

more they must approve them; and for that Purpose all they have to do,

is, to move them by some amorous dalliance to give them a transient

view of the pleasure they are afterwards to reap from the beloved object.

And secondly, to the young ladies that whatever beauties they discover

to their lovers, provided they grant not the last favor, they only ensure

their admirers the more; and by a glimpse of happiness captivate their

suitor the better. (Pamela Censured, 31-32) Pamela

Conduct in High Life, May 28, 1741 Following the procedure of the pamphlet, BW quotes

the same Pamela passage the Censurer has quoted, and asks rhetorically,

what is there in this passage to “kindle desire” or allow us to suppose

that Pamela fell into an “indecent posture”? “Well, but the warmth of

imagination in this virtuous Censurer supplies the rest.” So BW accuses

the Censurer of giving “an idea of Pamela’s hidden beauties, and would

have you imagine she lies in the most immodest posture.” Thus it is

the Censurer, not the editor/ author who endeavors “to impress [upon]

the minds of youth that read his Defense of Modesty and Virtue, Images

that may enflame.” Is

there any particular posture described? Oh, but the Censurer lays her

in one which may enflame, you must imagine as lusciously as he does;

if the Letter has not discovered enough, the pious Censurer lends a

hand, and endeavors to surfeit your sight by lifting the covering which

was left by the editor, and with the hand of a boisterous ravisher takes

the opportunity of Pamela’s being in a swoon to----But I am writing

to a lady, and shall leave his gross ideas to such as delight to regale

their sensuality on the most luscious and enflaming Images. (Kelly,

xv) from:

Pamela Censured After

some little tart repartees and sallies aiming at wit, the author seems

to indulge his genius with all the rapture of lascivious ingenuity:

‘I wish, said he, (I’m almost ashamed to write it,

impudent Gentleman as he is!) I wish, I had thee as QUICK ANOTHER WAY,

as thou art in thy repartees.--- And he laughed, and I snatched my hands

from him, and tripped away as fast I could....’ Here

virtue is encouraged with a vengeance and the most obscene idea expressed

by a double entendre, which falls little short of the coarsest ribaldry;

yet Pamela is designed to mend the Taste and manners of the Times,

and instruct and encourage youth in virtue; ... The

long defense of Pamela against its critics appended by Richardson

to the prefatory material in the 2nd edition (February 14,

1741), composed mostly from excerpts of letters from Aaron Hill, responds

to the letter of an anonymous critic of Pamela’s double entendres

with an appalled determination to ignore its criticism: “[this is] too

dirty for the rest of his Letter.... In the occasions he is pleased

to discover for jokes, I either find not, that he has any signification

at all, or such vulgar, course-tasted allusions to loose low-life Idioms,

that not to understand what he means, is both the cleanliest [sic],

and prudentest [sic] way of confuting him.”(16)

|

The problem of performance and theatricality:

how do you present virtue so it is not contaminated by the possibility

that this is a motivated performance? Chardin, The House of Cards Chardin, Boy Blowing Bubbles

Fragonard, the Reader

Fragonard, the Bolt • (Chardin ~ Richardson) depicting the simple souls

of the bourgeois home in states of absorption (writing, sorting clothes,

etc.) |

| William B.

Warner, Licensing Entertainment, Chapter

V: the Pamela Media Event (Note: this is an early unedited draft of the manuscript; it will not therefore always work for citation) |

| Denis Diderot, Eloge de Richardson, January 1762 |